Irving Vermilya

America's #1 Amateur

Donna L. Halper

If you were alive during the formative years of amateur radio, you knew Irving Vermilya. From the time he was 12 and he travelled with his dad and his family's minister to Canada to hear Marconi speak, amateur radio was his first love, and he was a life-long ambassador for it. (The story goes that after the talk, which was mainly attended by adults, Marconi came over to the young lad and encouraged him in his interest in wireless. He even gave young Irving a piece of equipment, which became Irving's first receiving set.)

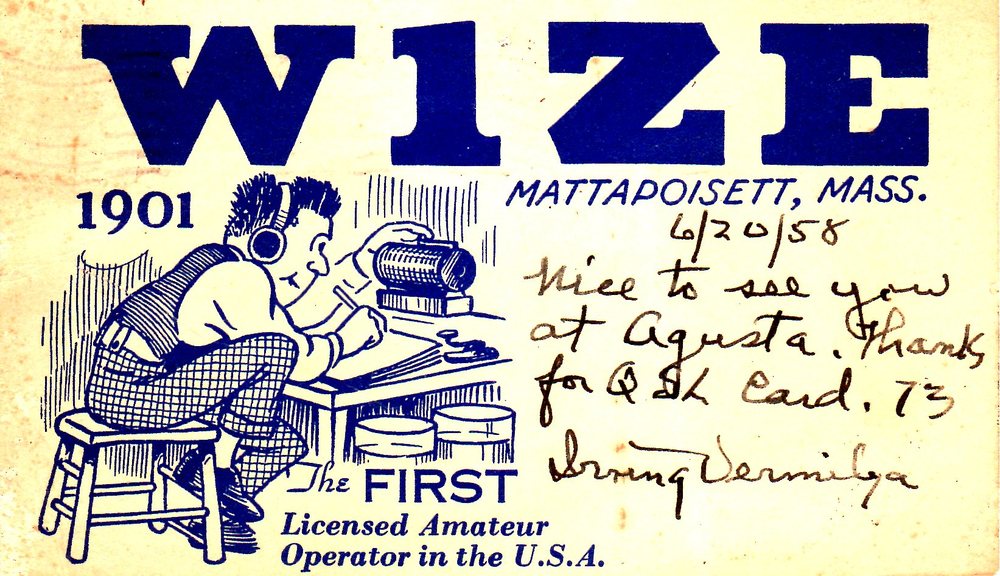

Born in June of 1890, Vermilya grew up in Mt. Vernon, New York, where he built that first rather primitive set in December of 1901, after returning from his trip to see Marconi (as he later recalled, it looked strange, but it worked). Other more advanced (and more professional-looking) sets followed, and his dedication to wireless increased. His spark transmissions were so frequently heard that he was offered jobs on ships that needed a wireless operator. He became a member of the newly formed Radio Club of America in 1911, using the calls VN. (Later, he would use 1HAA, but he was best known as W1-ZE). In late 1912, the government began to require that all wireless operators be licensed. Irving hurried to the Brooklyn Navy Yard to take the test, and was given Certificate of Skill #1. For the rest of his life, he would be known as America's Number 1 Amateur—which he truly was.

Irving Vermilya's involvement with radio continued; at the age of 16, he did in fact go to sea as a wireless operator; a few years later, he was given the important job of running the Marconi Wireless Station, WCC, on Cape Cod. During World War I, he served in the Navy, and then returned to Massachusetts to run the RCA wireless station at Marion. His engineering and wireless skills brought him into contact with such legendary figures as David Sarnoff, Lee DeForest, and Edwin Howard Armstrong.

By 1921, professional radio stations were springing up, and Irving was interested in this new technology too. Using his newly acquired license for a land station, 1ZE, he began doing radio broadcasts in late April (according to the Boston Traveler's ham radio column, he got special permission to be on even before he received the official license in May); his plan for 1ZE was to both promote amateur radio and to entertain his neighbours in and around New Bedford and upper Cape Cod with concerts and local information. His work came to the immediate attention of the Slocum and Kilburn Company, which was planning to open a station at their mill (the mill was similar to what we would call a “general store”, since it also sold electrical equipment, tools, and building supplies; the station would be located in the radio department). They hired Irving to build it and run it, and the station went on the air officially the last week of May 1922 as WDAU.

(A “cousin” of WDAU still exists, although today, it is known as WNBH; these initials stand for New Bedford Hotel, where its studios once were located. Interestingly, thanks to the consistent link of Irving Vermilya as owner or engineer, WNBH claims to be the 11th station in the US, tracing itself back to 1ZE in mid 1921 and then to WDAU. However, the evidence seems to suggest that while Irving worked at 1ZE, WDAU, amd WBBG, the first two never directly evolved into WNBH. 1ZE remained on the air, in fact, long after he was hired to build WDAU. 1ZE was renamed by the government as W1-ZE, but Irving still owned and operated this well-respected ham station for over 40 years. Slocum & Kilburn kept WDAU on the air briefly even after Irving left to put WBBG on. It was WBBG that really evolved into WNBH; the station first began to broadcast under those calls in early November of 1925. But being the 11th station in the US makes a great story, and it has been repeatedly stated as a fact both by WNBH and by the New Bedford media. Given Irving Vermilya's many achievements, it doesn't surprise me that he receives credit for one that may not totally be accurate.)

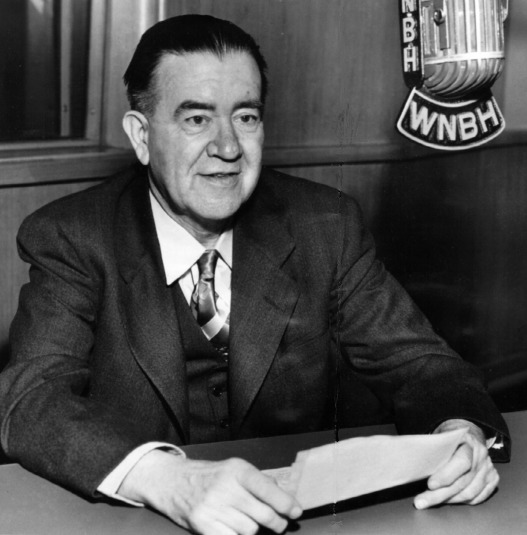

When financial problems beset Slocum and Kilburn in late 1923, Irving acquired the station's equipment and moved it to his house (imagine his wife's surprise) in January of 1924. He began to operate it under the call letters WBBG until mid-1925. (His was one of many small stations that suffered when ASCAP required all stations, no matter what their size, to pay large fees to play ASCAP music; such fees almost drove Irving's little station off the air, but it made him even more determined to find some financial backers so that he could keep the station operating.) He was finally able, with business partner and fellow ham radio operator, Armand J. Lopez, to move his radio station back to New Bedford in November of 1925, requesting the aforementioned WNBH call letters. It was common in radio's early days for stations to have studios at hotels, since this provided a studio audience as well as a house dance band, and it certainly gave WNBH a good community image to have the hotel as its location. Irving continued to play a major role in WNBH's operation, serving as its General Manager, as well as helping to hire the talent and getting the station publicity. His ability as an engineer was well-known, and he frequently kept the station up and running during winter storms or other weather-related problems. In May of 1934, he sold WNBH to the owners of the New Bedford Standard-Times newspaper, but he continued to work there, first as station manager and later as the chief engineer until he retired in 1955.

While Irving Vermilya's career in professional radio earned him considerable praise, he never stopped being involved with ham radio. In 1921, he was named the New England Manager of the ARRL. He was the mentor to Eunice Randall, the district's first woman amateur, and at a time when women were not expected to know anything about radio, Irving was totally supportive of Eunice and encouraged other men to give her a chance—Irving and Eunice were friends for many years, participating in various conventions together, and of course, keeping in touch via their ham sets. Irving wrote columns on ham radio for QST and for various newspapers, and won virtually every award a ham could win—it was impossible to read any magazine about ham radio without seeing another country or continent that W1-ZE had received or been received by. (In the early 1920s, amateur ‘tests’ were often held to see how far a transmission could go, and Irving was one of the few whose messages were received as far away as Europe.) And as you might expect, he also put a mobile transmitter in his car, and in the early 1930s, he set up the first police radio station for the New Bedford Police department (WPFN). In fact, whenever he could put his radio skills to a positive use, Irving was right there to volunteer, whether it was relaying messages during a hurricane or attracting some publicity for ham radio by engaging in a “foot-sending” contest with Eunice Randall (Eunice usually won). Years later, he was one of the founding members of the Old Old Timers Club, and served on its board. He was also the first American citizen ever given a permit to operate his mobile station in Canada.

I would like to tell you that such a distinguished career and such a highly respected man lived to a ripe old age, but not every story has a Hollywood ending. Depressed by the death of his wife, in failing health, and perhaps feeling the radio industry no longer had a place for him, in late January 1964, Irving Vermilya committed suicide. His death came as a shock to the many people who had admired him; even the Standard-Times editorialized about what a fine human being he was, and how much he had contributed to broadcasting. Irving Vermilya elevated the status of ham radio, and was an able spokesperson and emissary, whose outgoing personality made friends wherever he went. If it were not for him, New Bedford and large parts of Cape Cod would not have had a professional radio station until the 1930s, and thousands of people who met him via ham radio would not have known what fun this hobby could be. He was a strong believer in community involvement, and whatever station he ran, be it amateur or profession, it would always do its part to help the community. Perhaps he never invented something major the way Marconi did, perhaps his name is not as famous as Sarnoff's, but it is radio's early pioneers who paved the way for the fledgeling industry to grow and succeed. Irving Vermilya devoted his life to radio, and he deserves our thanks for that dedication and his many years of service to the industry he loved so much.